Pavarotti And Verdi: The Essential Operas

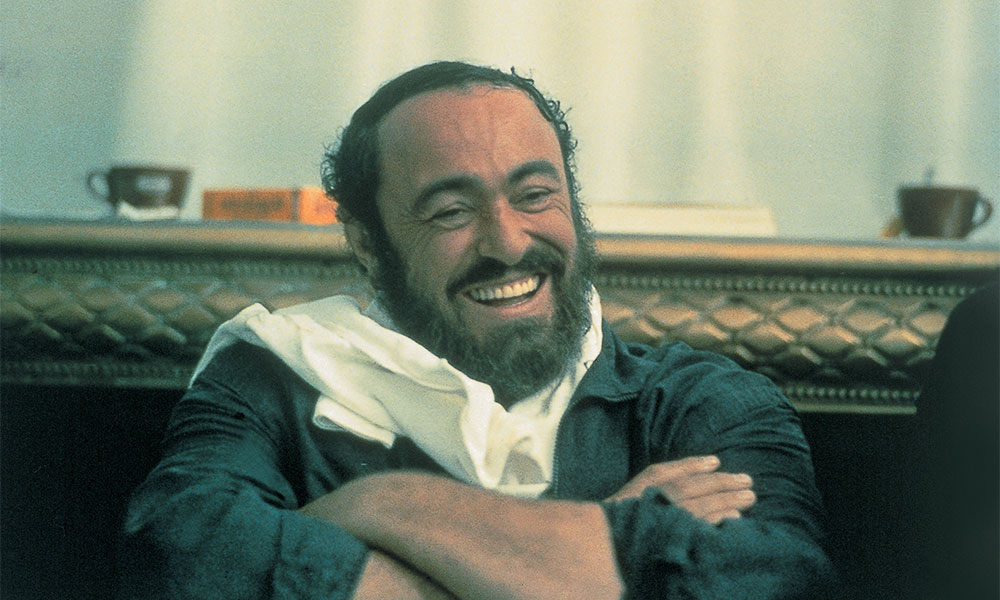

Pavarotti was supremely canny when it came to repertoire. He knew that Italian works suited him best – he sang almost nothing else – and within that repertoire, he stuck with only a handful of nineteenth-century composers. And even then, he mostly performed only their masterpieces and not their also-ran curiosities. It’s what helped his career to last as long as it did. One of the composers he turned to again and again was Verdi, and it’s not hard to hear why. Verdi had the common touch – just like Pavarotti. Verdi loved melody – just like Pavarotti. Verdi was both deceptively simple and fascinatingly complex – just like Pavarotti. Scroll down to read our guide to the essential Pavarotti and Verdi operas and hear a match made in heaven.

Listen to Pavarotti: Music From The Motion Picture on Apple Music and Spotify.

Rigoletto

Even people who know nothing about opera can usually be counted on to recognize (and possibly even hum) the oom-pa-pa tune to “La Donna è Mobile” (it means “All Women Are Fickle”) from Rigoletto, an essential Pavarotti and Verdi opera. And it’s a stroke of genius that Verdi gives such a rollicking tune to such a thoroughly rotten character. He makes you sympathize with the Duke of Mantua – a cruel, callow womanizer – by sheer force of the joyous, ear-grabbing energy of this melody. Pavarotti made four recordings of the opera over the course of his career, and is splendid in all of them. But for my money, the earliest, from 1971 shows him at his best. He captures all the boyish charm, egotistical ease, and selfish glamour of the Duke and, just as the composer intended, forces you thrill to his unbridled energy. It doesn’t hurt either that the recording features Joan Sutherland as the heroine. As well as being superb in the role, she was one of the first artists to spot Pavarotti’s potential at the beginning of his career, and gave him several important opportunities. They remained firm friends, and the closeness of their artistic bond is palpable.

Click to load video

Il Trovatore

The role of Manrico in Il Trovatore (The Troubadour) is a far cry from the selfish-but-irresistible charm of the Duke of Mantua. Manrico is a tortured hero in the Byronic mold, who fights injustice and suffers for love. And though many suggested that the role was too heavy for Pavarotti, whose voice was initially considered attractively light rather than weighty and dramatic, he proved his naysayers wrong with his terrific fresh-as-paint first recording from 1976. In the aria “Di Quella Pira” (“The Flames From The Pyre”) from the end of Act 3, Manrico has just learned that his mother is about to be burned at the stake by his enemy, and vows to brave death to rescue her. Pavarotti goes full throttle, and really rattles the rafters with a long climactic top C as he dashes off to save his mum.

Click to load video

La Traviata

The role of Alfredo in La Traviata (The Fallen Woman), an essential Pavarotti and Verdi opera, is something of a cross between the Duke of Mantua and Manrico. Although musically speaking, it’s a light lyric role like the former, it contains elements of desperation and tragedy of the latter. Dramatically, too, we see the character journey from the selfishness of one to the self-awareness of the other. Pavarotti recorded the role twice, and, once again, the earlier just pips to the post, and reveals the tenor bursting with vitality and ardor. Just listen to how he floats his phrases with happiness in the aria “Dei Miei Bollenti Spiriti” (“My Buoyant Spirits”), and then switches to something more urgent for the second part “O Mio Rimorso!” (“O, My Remorse!”) when he learns that his noble lover has had to sell all her possessions to support their lifestyle. And prepare your spine to tingle at that fabulous top C at the end.

Click to load video

Aida

Verdi wrote a handful of supremely challenging entrance arias for his tenor characters (the one in Don Carlo is every singer’s nightmare) but none quite so cruel as “Celeste Aida” (“Heavenly Aida”). The warrior Radamès has only been on stage a few minutes when he has to launch into this rapt hymn of praise to the woman he loves. Its ecstatic melody pulses with breathless longing and endlessly spun-out phrases, and taxes every last drop of the singer’s stamina – and then he has to complete the rest of the opera. Naughty Verdi, eh? Pavarotti’s recording from 1986 is a masterclass in how to make it all sound effortless, and it finishes with a high top B flat which gets quieter the longer it goes on. Only a handful of tenors ever bother to follow Verdi’s marking here, and although Pavarotti doesn’t quite make it to the composer’s near-unattainable marking of pppp (quieter than a whisper) he goes as quiet as humanly possible, and the effect is miraculous.

Click to load video

Pavarotti: Music From The Motion Picture is out now and can be bought here.