The Sinister Urge: How The Marriage Of Metal And Horror Terrified The World

Heavy metal and horror have co-existed with one another from the former’s very inception. While the Bela Lugosis and Boris Karloffs of this world had long since had people filling their pants with last night’s dinner, their films never really had soundtracks as visceral as the action on screen. And while the relationship metal and horror has, in recent decades, birthed masked men, anti-Christ superstars, and pornographic, bank-robbing Germans, it’s vital to point out that metal’s unholy union with all things macabre was set in the stone from its first notes.

The 70s And 80s

While the That’s Not Metal podcast is named, ironically, after the fact that nobody can agree on what is and isn’t metal in the modern era, one of the very few things metal fans agree upon is that Black Sabbath is the starting point for the genre. A hipster or two might suggest Blue Cheer, and your dad might say Led Zeppelin, but the essence of what the world would come to know as heavy metal was formed by four blokes from Birmingham with a taste for the darker side of life.

A grand statement such as that demands a grand entrance – and the opening notes to the song “Black Sabbath” are a perfect indicator of where the relationship between heavy metal and horror was headed. The song may have come to fruition in the era of flower power, peace, and brotherly love, but take a second to consider this: its intro remains ominous yet threatening, eerie yet thunderous to this day. The song’s opening lines, “What is this that stands before me? Figure in black that points at me,” doesn’t even need that body-chilling soundtrack to conjure images of his Satanic majesty baying for payment for whatever you looked at online last night.

Sabbath themselves may have only flirted with the Devil (Tony Iommi would wear a cross onstage and the band was keen to point out that they had only ever dabbled in occultism), but their status as the fathers of both heavy metal’s sound and its thematic focus is plain from the very beginning.

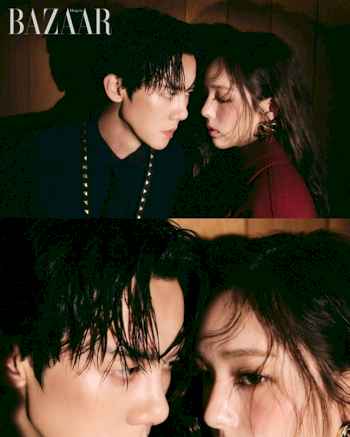

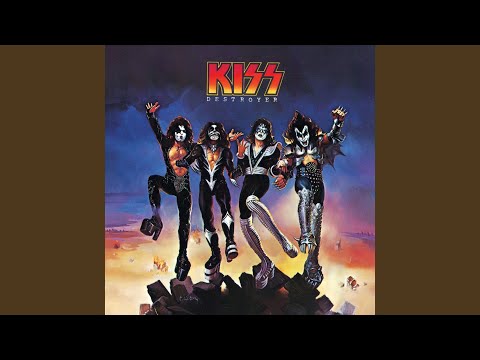

When most people think of heavy metal and horror, though, they think less about the actual devilish, murderous side of the latter and focus on bands far more theatrical than Sabbath. Here’s where it gets really interesting. There are two artists that define this era for metal and horror: KISS and Alice Cooper; the good guys and the self-appointed villain.

Let’s take the film Nightmare On Elm Street for a second. If you look at Freddy Krueger in the original movie, he is a genuinely hideous figure with the backstory of being a serial killer burned alive at a power plant. It’s a far cry from the cuddly, cutesy Freddy who would turn up on children’s lunch boxes and novelty items further down the line, but Krueger was a terrifying yet captivating figure for children in the 80s.

No strangers to appearing on lunch boxes themselves, KISS was a similar source of wonder for young heavy metal fans. If Sabbath and Alice Cooper set out to scare anybody, they could make eye contact with, KISS was all about spectacle: sassy Paul Stanley, the Star Child who could preen and pose with Tony Stark; Gene Simmons’ Demon, larger than life and thudding along to “God Of Thunder.” Listen to that song. Tell us that isn’t the sound of The Hulk pulverizing your neighborhood and causing the piercing screams of all who stand in his path. Ace Frehley, the Space Ace? Thor’s from space. You know we’re right about this.

Click to load video

Alice Cooper is a different story. KISS may have suffered a million squealing parents trying to suggest their name stood for Knights In Satan’s Service (something far more malevolent than KISS themselves would ever put forth), but to look at Alice Cooper’s carnival-of-terror live show was to see the blueprint for a marriage of metal and horror that would rage for the rest of time, from his unofficial protégés Marilyn Manson and Rob Zombie through to Rammstein, Slipknot and beyond. Why was Alice Cooper more threatening than KISS? Gene spat blood, but you can see worse than that in a boxing ring. Alice Cooper, meanwhile, was putting his head in a full-sized guillotine, decapitating himself and then doing “School’s Out” as an encore.

It’s funny to think that at the start of the relationship between metal and horror in the 80s, the scariest band would be Mötley Crüe. Their image may have defined them as a big-haired stripper-enticing, eight-legged, drinking riot machine, but it was the group’s earlier beckoning of the beast that would capture the minds of a generation of future rock stars.

From its title alone, their 1983 album, Shout At The Devil, bears all the hallmarks of a metal and horror crossover. The pentagram on the album artwork was crucial: this was a time when doing things like that was still taboo and likely to land you in hot water in whatever conservative town you rolled into next. And the album’s intro was a freakish, menacing prophecy of an impending apocalypse. Mötley Crüe’s look may have been inspired by an action movie the likes of Mad Max, but the video for “Looks That Kill’ hinted at a primitive ritual sacrifice in pure Wicker Man territory… albeit staged in a Revlon factory.

In the underground, Venom would take things into an altogether more religiously contemptuous zone. While sounding faster and harder than anything discussed here (think Motörhead being thrown into the blades of an active combine harvester), Venom would also be the first metal act to write openly Satanic lyrics, influencing everyone from 80s bands such as Possessed and Slayer, to 21st-century metal behemoths Cradle Of Filth and… er…Behemoth.

Click to load video

As Alice Cooper was to KISS in the 70s, the bigger extravaganza and character in the story of metal and horror in the 80s is Mercyful Fate frontman, and legend in his own right, King Diamond. Retrospectively camp and as fun as a night on the unholy water with Linda Blair, King Diamond’s inverted-crucifix microphone and his odes to the dark lord are one of metal’s most beloved horror shows; to this day, his live performances remain must-see events. The King may look like he’s a character from Hotel Transylvania made flesh, but back in the 80s people actually believed he lived in a coffin. We’re not joking.

Up to this point, metal and horror had enjoyed a steamy session together, but the cultural shift of Live Aid made a colossal impact. In one fell swoop, the (out-of-this) world of David Bowie and fellow god-like musicians came toppling down and music-making became humanized, such was the world-humbling effect of what remains one of the biggest concerts of all time.

So where do we go from here? As the 80s became the 90s, parents were distressed by a different kind of beast. For those who’d missed Bowie in the 70s, Perry Farrell looked like a sexy alien that was as attractive to men as he was to women. Try being a kid in Alabama, walking around with a copy of Jane’s Addiction’s Nothing’s Shocking, and pretend you wouldn’t get a horrified reaction.

Nine Inch Nails were also beginning to ramp up their cyber-mafia vibes, but they were still a world away from the band that would go on to make the “Happiness In Slavery” video. If you’ve never seen it (the video was banned by MTV), it’s influenced by David Lynch’s mind-warping black-and-white classic Eraserhead, and it achieved everything the movie Hostel managed a full 13 years before that movie arrived.

Click to load video

The 90s

The start of the 90s brought about the most significant change in the world of rock since, possibly, The Beatles first arrived on the scene. Nirvana and the grunge explosion’s scorched-earth policy towards rock and metal’s previous tropes meant that the fantastical bombast and excesses of the past were replaced almost overnight by a much more insular, personal, and stark image.

This changing of the guard brought a unique set of problems to any band that wished to indulge themselves in a horror aesthetic that was now considered passé. The answer to some, however, was to ramp the influence up even further.

Death metal had an easier time integrating than most. The musicians certainly conformed to the jeans-and-T-shirt image of the time, and their music was a dank, brutal, and new-sounding enough to stop them sounding like throwbacks or dinosaurs. But it was the lyrical and visual extremities of the early 90s Floridan death metal scene that pushed the mix of metal and horror even further. The likes of Obituary and, especially, Cannibal Corpse eschewed the complex, arcane mysticism of Morbid Angel and instead embraced the kind of shockingly graphic iconography you’d expect from a video nasty. Whether it was the album artwork of Eaten Back To Life or the lyrics on songs such as “A Skull Full Of Maggots,” “Submerged In Boiling Flesh,” or “Chopped In Half,” it was clear that death metal intended to set the bar for truly horrifying subject matter.

Not everyone balked at the idea of dressing up. Richmond, Virginia’s GWAR were one such band, styling themselves as a group of interplanetary warriors whose shows were as vulgar as anything that had been seen in rock until that point. Dressed in huge monster costumes, the band performed gigs full of slime, blood, and massive phalluses shooting semen. Though musically they were rudimentary, and their scatological humor and over-the-top shows were considered a joke by most, GWAR did achieve a level of notoriety due to the graphic violence displayed onstage.

While GWAR, and contemporaries such as Green Jelly, were considered a novelty, there was one band in the early 90s who truly managed to meld schlock-horror with genuine musical excellence: New York’s White Zombie. Starting out in the mid-80s as an art-punk project, by the 90s White Zombie had signed to a major label and honed their craft to the point where they could appeal to both metal and alternative fans, while leaning heavily on a horror aesthetic. Their finest moment is 1995’s Astro Creep: 2000 album, which created something utterly unique from a mix of industrial electronics, big metal riffs and samples from 50s horror and sci-fiction B-movies. White Zombie were the first band to take Misfits’ blueprint of Ramones’ musical simplicity mixed with 50s drive-in cinema and give it both a throbbing electronic update and a Technicolor, grindhouse visual makeover. The band split in 1996, leaving frontman Rob Zombie to push his marriage of horror and metal even further with his solo material, but the impact of White Zombie was undoubtedly huge.

Click to load video

Grunge wasn’t the only movement gathering momentum in the 90s. The success of movies such as The Crow meant that goth culture had a significant rebirth during this time. The first band to experience success from this scene where Type O Negative, one of the most uncharacterizable bands in the history of rock. Driven by dry, sardonic wit and led by the hulking, fang-wearing, Boris Karloff-esque Peter Steele, Type O Negative poked fun at gothic imagery by completely indulging themselves in it. On the surface, songs such as “Christian Woman’ or “Wolf Moon’ could be looked at as typical goth fare, but, in truth, they had their tongue rammed firmly in their cheek. Whether you were in on the joke or not, Type O Negative was gloriously spooky, full of unsettling, atmospheric keys, dark drama, and Steele’s deep, haunting baritone.

It would also be tempting to also look to the first wave of Norwegian black metal when considering horror’s impact on metal, but that may be to miss the point of the movement. The young men that formed bands on the back of their love for Bathory, Celtic Frost, and Venom looked the part with their corpse paint and dedication to the Satanic arts (bolstered by a genuinely pathological hatred of religion). But the insular nature that came to define black metal, and the rules that came with it, show that this was a group more interested in impressing its peers than aping the look of their favorite films.

Were it not for these bands, however, we may never have had the UK’s most notorious act of the era: Suffolk’s Cradle Of Filth. Taking their musical queues from Norwegian black metal, Cradle was less interested in Scandinavian mythology than they were in the words of Bram Stoker or Mary Shelley. An aura of romantic, poetic, Victorian, gothic flair surrounded the group: everything from their Lovecraftian lyrical strands to the band’s videos, which harked back to classic British Hammer Horror – albeit set to a far more graphic and brutal 90s standard.

But there is no doubting who the real boogeyman of the era was. Brian Warner christened himself Marilyn Manson after criminal cult leader Charles Manson and Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe, two of the most recognizable names of the 60s, and went on to terrorize mainstream sensibilities throughout the 90s. Manson was often compared to Alice Cooper, but where there was a clear and distinct line that could be drawn between Cooper and the real-life Vincent Furnier, Warner all but disappeared the day Manson arrived. There was nothing cartoonish or tongue-in-cheek about Manson. His genuine disgust of authority figures manifested itself in live shows that featured self-harm and Bible destruction, leading to public outrage, religious protests, and death threats. The “moral guardians” of the time queued up to loudly proclaim Manson the biggest threat to polite society America had ever seen.

Manson himself rode the controversy perfectly, cultivating an image that borrowed heavily from the church, the Third Reich, and from gothic and pagan iconography: the perfect amalgam of metal and horror yet conjured in their 30-year dance together, hulked up to shocking new levels. His live shows passed into legend as stories of Manson’s debauched onstage behavior grew wilder with every retelling, and he was happy to appear in plain sight on popular talk shows such as Bill Mahr’s Politically Incorrect, articulately debating his position alongside activists, political commentators and members of Congress. The more Manson was derided the stronger he became, with a cult of young fans aping his look and hanging on his every word.

By the late 90s, Manson had brought back the idea that rock music could be larger than life, and, alongside the influence of nu-metal godfathers Korn, he became the most obviously copied artist of the era. Suddenly there was a group of androgynous, industrial-tinged weirdos on every corner. From Orgy to Powerman 5000 and Coal Chamber (who patented their own genre, spookycore, to describe their goth-kid-chucked-through-a-paint-factory look), what was dangerous and subversive in the hands of Manson had become ludicrously formulaic and utterly PG13. Horror’s influence was now more Monster Squad than Nightmare On Elm Street.

Many wondered if the envelope had been pushed as far and as hard as it could have been, but then a group from Des Moines, Iowa, took the sly, sexual, cold-blooded reptilian vibe of Manson and turned it into the bloodthirsty, uncontrolled attack of a rabid wolf, multiplied that by nine and unleashed a brand of music that took the sheer, guttural, brutal hatred of death metal and made it angrier, more real and, most importantly, available for all to see in the flesh. Slipknot’s self-titled debut album, released in late 1999, sent a seismic shift throughout the metal scene. If Manson was The Exorcist, then Slipknot was The Last House On The Left, and they were about to scare everyone all over again.

Click to load video

The 21st Century

Both metal and horror found themselves at a crossroads as they left the 20th Century behind, and both were about to find new ways to terrify and electrify their audiences. Horror revitalized old tropes, with 28 Days Later giving a much-needed jolt to the tired zombie genre, and Japanese exports Ring and The Grudge doing the same for ghost stories, while a wave of so-called “torture porn” was on the horizon. Metal, meanwhile, did something similar. Gradually freeing itself from the dying grip of nu-metal, newer acts turned to modern takes on metal’s more traditional ideals, while the first signs of the emo boom began to pop up throughout rock. As the 21st Century dawned, the worlds of metal and horror seemed as closely intertwined as ever.

Having released their self-titled debut album in 1999, Slipknot charged into the new millennium with the force of a small planet. Delivering a major blow to nu-metal by being so terrifying that everyone else looked a bit rubbish, the horror DNA in Slipknot was blindingly obvious, the band looking like they’d stumbled offset from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and started abusing whatever random instruments they found first.

Click to load video

Unsurprisingly, plenty of bands followed suit. Avenged Sevenfold are metal’s big post-Slipknot success story, and on their 2003 breakthrough, Waking The Fallen, they packed a crypt-crawling look like the Misfits of metalcore. Even after they recalibrated themselves to sound something closer to Guns N’ Roses’ hard rock pomp, the group’s Deathbat logo remained. And as anyone who’s seen them live can tell you, watching an arena full of people yelling every word of twisted necrophiliac love story “A Little Piece Of Heaven” provides the kind of sick thrill only horror can. At the same time, My Chemical Romance was starting to make a name for themselves with an aesthetic that wasn’t explicitly horror to the same extent, but still had enough vampiric flair to make them feel the gang of spooky kids they were – something which has since translated into today’s Britrock leading lights, Creeper.

Despite these mainstream successes, horror is always going to thrive most in the underground. Following in the footsteps of such pioneers as Death, Autopsy, and Cannibal Corpse, a new generation of death metal bands quickly made brutality their own. The Black Dahlia Murder is the natural successor to the goresmiths of old, their vocalist Trevor Strnad combining the flamboyant dark poeticism of Cradle Of Filth’s Dani Filth with a nastier taste for traditional death metal depravity that has made his band one of the premier outfits for lovers of the macabre. Amid songs full of zombies, demons, and mutilation, Strnad embodies the characters in his lyrics with the genuine skill of any actor, reveling in eating the preserved remains of his murder victims on “Jars” as “each one encapsulates a visage of that fateful night of those who met their end by my ever still and sharpened skinning knife”.

In the age of the internet, where access to music is democratized for listeners and artists are able to put their work out there without necessarily having to get past any filters other than their own, the boundaries of what is acceptable to portray within music – and where the relationship between metal and horror may yet lead – have been pushed further than ever before. Nowhere is this more prominent than in the shadowy world of brutal death metal and goregrind: an entire scene that, for the most part, is never even touched by the rock and metal press. And, frankly, it’s not hard to see why. One look at the artworks and tracklists of Regurgitate’s Carnivous Erection, Impaled’s The Dead Shall Remain Dead, and Vulvectomy’s Abusing Dismembered Beauties tells you all you need to know, to the point of raising a moral debate even in today’s increasingly desensitized world.

The relationship between metal and horror thrived during the golden age of the music video, and while the format has generally declined in importance in the last decade, that hasn’t stopped bands with a morbid streak from trying to make an impression. In a perfect example of how boundary-pushing bands have used new tools to get around previously unsurmountable obstacles, Cattle Decapitation’s video for “Forced Gender Reassignment” has become the stuff of legend in underground circles for being one of the last things to truly shock people on a notable scale. When both YouTube and Vimeo rejected the video on account of its exceptionally graphic content (if you’re tempted to find it, be warned: it’s really not for the faint of heart), the place that stepped up to host it was BloodyDisgusting.com – one of the internet’s largest dedicated horror sites.

Click to load video

The crossover between metal and horror, however, isn’t just limited to underground bloodbaths. Unquestionably the best example of metal and horror’s unholy matrimony today comes in the shape of the pelvis-thrusting, orgasm-encouraging, satanic majesty of Ghost.

Lead by the various guises of Papa Emeritus, the Swedish rockers may be closer in sound to Blue Öyster Cult and Blackfoot than they are anything remotely contemporary, but their fresh approach to occult horror walks a perfect line between the old-school hijinks of Rosemary’s Baby and new-school chill-fest The Witch. It also helps that they’re one of the best bands on earth. Well, they do say the devil has all the best tunes.

In the mainstream, meanwhile, Bring Me the Horizon dove into more commercial waters with the album That’s The Spirit, but they still decided to turn themselves into exceptionally hairy werewolves and eat each other in the “Drown” video. Elsewhere, PVRIS has adopted a gothic style that counterbalances their synth-pop-laced music; their video for “White Noise’ is essentially a four-minute recreation of Poltergeist, with bonus horror reference points going for Lynn Gunn being dragged up the walls by an unseen force, Nightmare On Elm Street-style.

With the level playing field that the internet provides, and the countless subgenres and scenes that rock music has splintered into, there comes an endless number of ways in which to handle an aesthetic. Metal and horror integrate in more diverse ways than ever, even if the results aren’t as moral-panic-inducing as Marilyn Manson or Alice Cooper were in the past. Tribulation draw on 20s silent horror cinema to give their vampirism a refined and effeminate feel; Electric Wizard keeps Sabbath’s original spirit alive with added Satan and Lovecraft; and the synthwave movement that has unexpectedly aligned itself with rock proudly bears the mark of John Carpenter.

Metal and horror may never again combine to shock the world the way it did in the past, but that Slipknot, Avenged Sevenfold, and My Chemical Romance became some of the biggest rock bands of the millennium says a lot about the dark side’s enduring ability to entice and consume.

Looking for more? Discover the best Halloween songs of all time.