‘State Of The Tenor, Volume 2’: Joe Henderson At His Absolute Peak

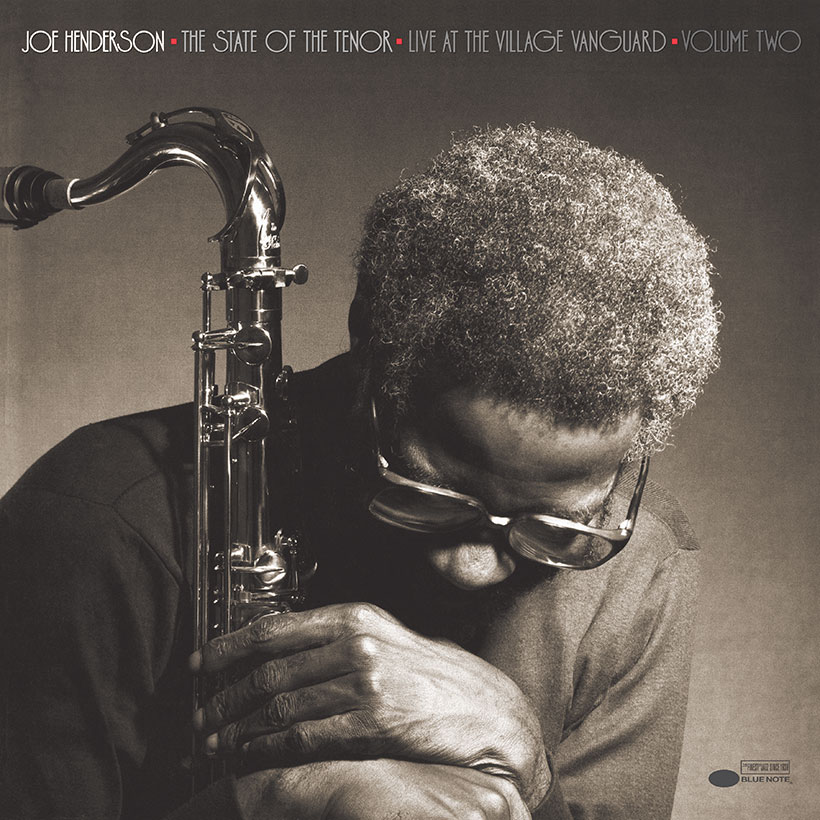

The second of two albums compiled from recordings made at the celebrated New York jazz club Village Vanguard, State Of The Tenor: Live At The Village Vanguard, Volume 2 captures the bearded and bespectacled Midwest tenor Joe Henderson on the nights of November 14-16, 1985.

Seven of Henderson’s performances from those nights – where he received stellar accompaniment from bassist Ron Carter and drummer Al Foster, both ex-Miles Davis sidemen and legends of their respective instruments – were issued by Blue Note Records on an album called State Of The Tenor: Live At The Village Vanguard, Volume 1, in 1986. It received such huge acclaim from critics and fans that it was inevitable, perhaps, that a second volume would appear. Blue Note duly obliged, releasing a second and final instalment the following year.

Listen to both volumes of State Of The Tenor: Live At The Village Vanguard on Apple Music and Spotify.

By the mid-80s, Joe Henderson, originally from Lima, Ohio, was 42 years old but already assured of a place in the pantheon of great jazz saxophonists. Renowned for combining a husky growling tone with soulful sophistication, Henderson had made his debut as a leader with Blue Note back in 1963, with the album Page One, which began a fertile four-year spell with Alfred Lion’s label, culminating with 1966’s classic Mode For Joe. After that, Henderson enjoyed a long sting at Milestone Records, though the late 70s found him freelancing for several different smaller companies.

Still a force to be reckoned with

The first volume of State Of The Tenor not only reunited Henderson with Blue Note (which at that point in its history had been spectacularly revived under the stewardship of Bruce Lundvall) but was also the first album released under Henderson’s own name after a four-year recording drought. The recordings from those Village Vanguard concerts in 1985 showed that Henderson was at the peak of his creative powers. While the first volume of State Of The Tenor confirmed that Joe Henderson was still a force to be reckoned with in jazz, the second volume served to underline that impression while also satisfying the need of those who wanted to hear more material from the concerts.

Yet State Of The Tenor, Volume 2 cannot be dismissed as a collection of leftovers. The reason why its six tracks were omitted from Volume 1 seems more to do with the taste of the album’s producer (and noted US jazz critic) Stanley Crouch.

Interestingly, in the original liner notes to the first volume, Crouch likens Henderson’s Village Vanguard concerts to “saxophone lessons”, on account of the number of horn players that were in the audience that night. Certainly, Henderson gives a bona fide masterclass in terms of saxophone improvisation. And, like another tenor master, the great Sonny Rollins, who had recorded a live album for Blue Note at the very same venue 28 years earlier (1957’s A Night At The Village Vanguard), Henderson found that the absence of a chordal instrument (such as a piano or guitar) allowed him greater melodic and harmonic freedom.

That sense of liberty is evident on Volume 2’s opener, “Boo Boo’s Birthday,” Henderson’s retooling of a tricky composition by Thelonious Monk (which the pianist/composer had written for his daughter). Ron Carter and Al Foster create a gently undulating rhythmic backdrop over which Henderson takes Monk’s jagged, asymmetrical melodies and explores them fully with a series of snaking improvisations. Ron Carter also demonstrates his bass prowess with a solo that is supple yet eloquent, but which keeps propeling the song forward.

Click to load video

Soulful and versatile

Another cover, Charlie Parker’s “Cheryl,” is given the Henderson treatment but initially opens with a short Carter bass solo before the tenor saxophone enters and states the main theme. He then embarks on a long passage of extemporization defined by breathtaking melodic slaloms.

“Y Ya La Quiero” is a Henderson original first recorded as “Y Todavia La Quiero” for his 1981 album, Relaxin’ At Camarillo. In terms of its loping bass line and sequence of four repeated chords, the tune bears an uncanny resemblance to Pharaoh Sanders’ spiritual jazz classic “Hum Allah Hum Allah Hum Allah” from his 1969 album Jewels Of Thought. It begins with a high fluttering tremolo from Henderson’s saxophone, before he enunciates a dancing theme under Carter’s fulcrum-like bass and Foster’s pulsing hi-hat figures. Arguably the high point of State Of The Tenor, Volume 2, “Y Ya La Quiero” shows Henderson’s versatility and his ability to play in a more avant-garde style – using shrieks and overtone-laden growls – without losing the inherent soulfulness of his sound.

That soulfulness – and versatility – is also abundantly clear on “Soulville,” Henderson’s mellow but swinging take on an old Horace Silver tune from the pianist/composer’s 1957 Blue Note album, The Stylings Of Silver.

Another Silver tune, “Portrait,” co-written with jazz bass legend Charles Mingus, illustrates Henderson’s skill as a ballad player. His approach is gentle to the point of being delicate, but you can also sense a pent-up power that gives his melodic lines a robust muscularity.

Click to load video

Fresh momentum

Joe Henderson first unveiled the self-penned “The Bead Game” on his 1968 album Tetragon. The live rendition on State Of The Tenor, Volume 2 is not as frenetic, perhaps, as the original, though as it develops it certainly transmits a high-intensity post-bop approach to jazz. Henderson is nothing less than magisterial.

State Of The Tenor, Volume 2 has been remastered as part of Blue Note’s Tone Poet Audiophile Vinyl Reissue Series but, significantly, it’s the only title that hasn’t been sourced from an analog master. It was recorded digitally, as the “Tone Poet” himself, Joe Harley, revealed to uDiscover Music in December 2018: “It was recorded on a Mitsubishi X-80 machine,” he said, referring to a two-channel digital recorder that became popular in the early 80s. According to Harley, however, the music on the new vinyl edition of State Of The Tenor, Volume 2 sounds superior to the original. “It sounds amazing, even though it was initially recorded digitally,” Harley stated.

State Of The Tenor, Volume 2 helped to give fresh momentum to Joe Henderson’s career in the 80s, aiding his recognition as one of jazz’s major saxophonists. He left Blue Note soon after the album’s release and would see out the remainder of his career at Verve Records, between 1991 and 1997, before dying from emphysema at the age of 64, in 2001.

Anyone doubting Joe Henderson’s importance, his place in the lineage of great tenor saxophonists and the value of his musical legacy should listen intently to State Of The Tenor, Volume 2. It captures the tenor titan in blistering, spellbinding form. Or, as Harley succinctly put it: “I think it’s Joe Henderson at his absolute peak.”

The Tone Poet reissues can be bought here.