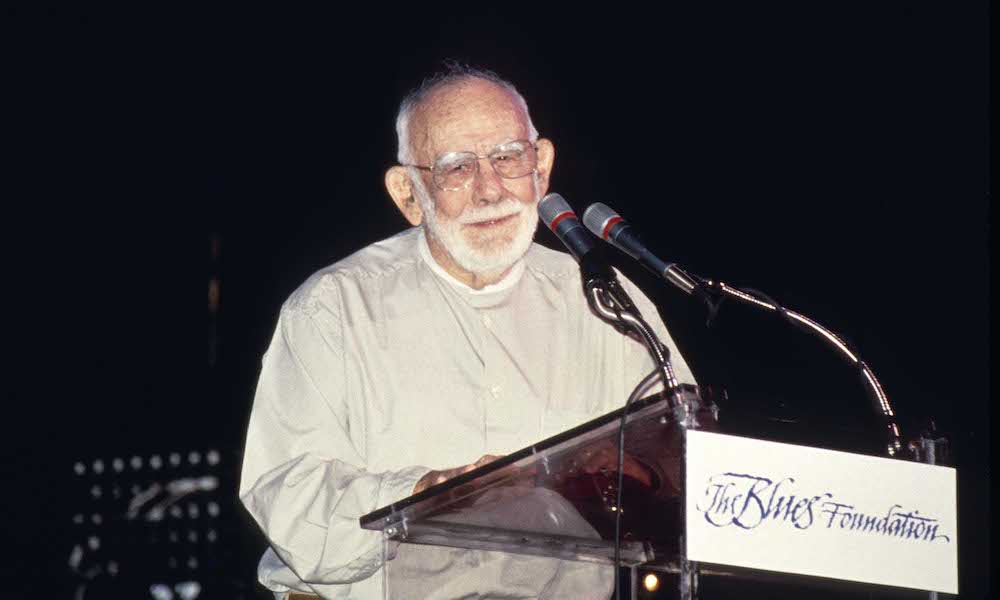

The Rhythm & The Blues: A Salute To Jerry Wexler

Plenty of record executives like to think they have changed the shape of popular music in one way or another. Jerry Wexler, born on January 10, 1917, not only changed its shape, he changed its name.

Wexler passed away in 2008 at the venerable age of 91, but we feel his influence on the modern music business now as we always will. As a journalist at Billboard magazine, this erudite individual from the Bronx came up with the very name “rhythm and blues,” before going on to help define it at Atlantic Records and far beyond.

Wexler got to Atlantic, who head-hunted him from Billboard, in 1953, becoming vice president of the burgeoning force in R&B music and overseeing the careers of such groundbreakers as Ray Charles and the Drifters. “We just never seemed to miss,” he told The Independent newspaper in 1993. “We had this incredible roster of repeating singers, and almost no one-hit wonders. We had certain standards of bel canto. We believed in singers and not just interpreters.”

Later, he was responsible for bringing the brilliant southern soul label Stax into the Atlantic fold, and did the same with such marques as Capricorn, Swan Song and Rolling Stones Records. By 1975, he was already telling Melody Maker: “One of our very happy acquisitions was the Rolling Stones, and we were glad to have the opportunity to make a contract with them. Without going into details, you can imagine they are expensive. The Stones are the group with the longest durability record and the greatest track record.”

As Atlantic evolved, so did he, but he was never far from the studio, sharing production responsibilities with his great friend Tom Dowd and bringing out the best in such singular and wide-ranging talents as Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, the Allman Brothers Band, Dusty Springfield, Cream and Led Zeppelin. Proudly incapable of seeing color, Wexler was one of a small band of industry mainstays able to judge a record purely by what was in the grooves.

“We are lucky in that so many of our artists are contributory,” he told the NME in 1969. “However great their talent, some artists do not contribute to a session apart from the performance. But what Dusty and Aretha have in common is that both of them are full of ideas and interest in what’s going on, and they really make the whole thing come alive. Remember, producers don’t really make records great. It’s the artist.”

Wexler’s talents thus extended far beyond the studio, but among the timeless to carry his production credit are the remarkable sequence he began with Franklin in 1967, when she came to Atlantic with I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Loved You). He famously supervised Springfield’s sessions that led to the seminal 1969 release Dusty In Memphis, and oversaw 1971’s self-titled second album by another Atlantic soul sensation, Donny Hathaway, along with the artist and Arif Mardin.

Click to load video

Wexler was at the desk for Delaney & Bonnie’s fourth studio set of 1970 and first for Atco/Atlantic, To Bonnie From Delaney. Later productions included Dire Straits’ second album Communiqué, which he helmed with Barry Beckett, and, the same year, Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming, which in turn featured Mark Knopfler. Later, in semi-retirement, he helmed Etta James’ 1992 set The Right Time.

The executive was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987, and maintained his close interest in the business, and his devotion to the power of the English language, even in his twilight years at home in Sarasota, Florida. “Wexler was much more than a top executive,” noted Rolling Stone on his death. “He was a national tastemaker and a prophet of roots and rhythm.”